A Visual Guide

"A GUIDE TO BERLIN" by V. Nabokov

Composed of five independent sections with a short preface, Nabokov's "A Guide to Berlin" appears to follow the generic norms structurally, but deviates from them thematically.

The unconventional nature of this "Guide" manifests itself in the very titles of the individual chapters: "The Pipes," "The Streetcar," "Work," "Eden," and "The Pub," only the last of which would be likely to appear in a traditional guide or a travelogue. The genre is further destablized by the use of elaborate style, intricate syntax, and figurative language. The story departs from the genre both in that it contains unconventional material and in that it endows quotidian objects with poeticism and artistic worth.

Using the power of his imagination and a keen awareness of the interconnectedness of time, the narrator transforms the city that his friend perceives as "boring, foreign," and "expensive to live in" into an artistic laboratory with a distinct topography.

The images below show the material space of 1920s Berlin—snapshots of the city's everyday existence. The excerpts from the story pertaining to the objects portrayed illustrate how the physical space of Berlin is transformed into fictional space through the narrator's use of imagination, memory, and art. My own comments are meant to elucidate the composition and significance of certain "transformations."

[The quotations from the text are italicized throughout, with emphases in bold added.]

"THE PIPES"

"In front of the house where I live a gigantic black pipe lies along the outer edge of the sidewalk. A couple of feet away, in the same file, lies another, then a third and a fourth—the street's iron entrails, still idle, not yet lowered into the ground, deep under the asphalt.

For the first few days after they were unloaded, with a hollow clanging, from trucks, little boys would run on the up and down and crawl on all fours through those round tunnels, but a week later nobody was playing any more and thick snow was faling instead;

and now, when, cautiously probing the treacherous glaze of the sidewalk with my thick rubberheeled stick, I go out in the flat gray light of early morning, an even stripe of fresh snow stretches along the upper side of each black pipe while up the interior slope at the very mouth of the pie which is nearest to the turn of the tracks, the reflection of a still illuminated tram sweeps up like bright-orange heat lightning.

Today someone wrote "Otto" with his finger on the strip of virgin snow and I though how beautifully that name, with its two soft o's flanking the pair of gentle consonants, suited the silent layer of snow upon that pipe with its two orifices and its tacit tunnel."

"THE STREETCAR"

A different kind of estrangement is performed in the second section of the guide that parallels the preceding description of the pipes and intersects with it in several points. Time serves as the main defamilizaring tool, and the idea of reflection, both in life and in art, is echoed here both thematically and structurally.

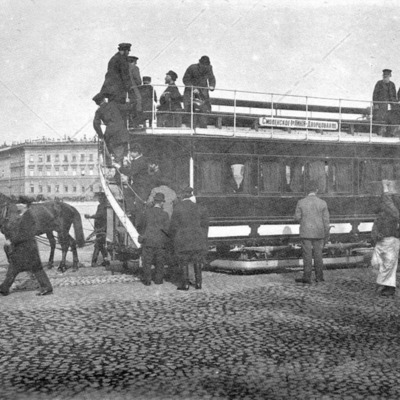

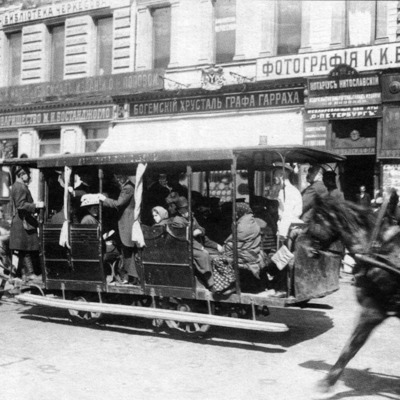

"The streetcar will vanish in twenty years or so, just as the horse-drawn tram has vanished. Already I feel it has an air of antiquity, a kind of old-fashioned charm."

The complex interplay and interconnectedness of time serves as the foundation for the narrator’s description of the streetcar. The present, past, and future interact in this section, as is evident in its opening sentence: “The streetcar will vanish in twenty years or so, just as the horse-drawn tram has vanished.” The first word “streetcar” can be seen as referring to the present, even though nouns lack the grammatical category of time. It is unlikely to denote the particular streetcar, which the narrator boarded on his way to the zoo. Rather, it signifies a general means of transportation in Berlin of the 1920s and refers thus to the present as that historical moment, in which the narrator lives. The sentence proceeds into a future when the streetcar will be obsolete; by introducing the already antiquated “horse-drawn tram” in the final clause, it draws a parallel between the object of the past and the thing of the present and reflects both through positing a future when both will be outdated, displayed in “a museum of technological history.”

"Everything about it is a little clumsy and rickety, and if a curve is taken a little too fast, and the trolley pole jumps the wire, and the conductor, or even one of the passengers, leans out over the car's stern, looks up, and jiggles the cord until the pole is back in place,

I always think that

the coach driver of old must sometimes have dropped his whip, reined in his four-horse team, sent after it the lad in long-skirted livery who sat beside him on the box and gave piercing blasst on his hown while, clattering over the cobblestones, the coach swung through a village."

"At the end of the line the front car uncouples, enters a siding, runs around the remaining one, and approaches it from behind. There is something reminiscent of a submissive female in the way the second car waits as the first, male, trolley, sending up a small crackling flame, rolls up and couples on.

And (minus the biological metaphor) I am reminded of how, some eighteen years ago in Petersburg, the horses used to be unhitched and led around the pot-bellied blue tram."

The relationship between the past, present, and future that is enacted in this section is one of mutually reflecting surfaces. The past enters the present in the form of thoughtful meditations, as when a ride on a Berlin streetcar compels the narrator to imagine a horse-drawn coach, and of personal reminiscences, as when the narrator is reminded of Petersburg’s blue trams.

"I think that here lies the sense of literary creation: to portray ordinary objects as they will be reflected in the kindly mirrors of future times; to find in objects around us the fragrant tenderness that only posterity will discern and appreciate in the far-off times when every trifle of our plain everyday life will become exquisite and festive in its own right: the times when a man who might put on the most ordinary jacket of today will be dressed up for an elegant masquerade."

"WORK"

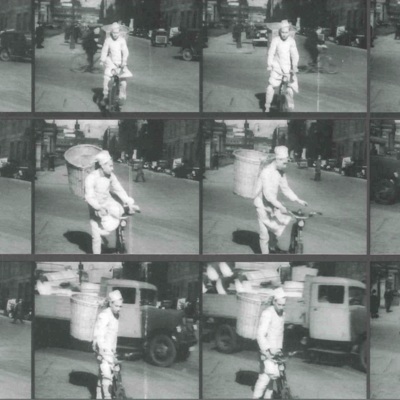

"Here are examples of various kinds of work that I observe from the crammed tram [...]"

Weaving his body through the urban texture, the narrator embraces the quotidian reality of the city and experiences it first-hand, describes the work of the people who live there, estranging even their everyday routine.

He focuses on the hands of the conductor on the streetcar, for example, and records, in great detail, a whole repertoire of the fast, virtuoso movements of his fingers. In the regularity of the four workers’ mallets pounding an iron stake while fixing the pavement, he discerns the musical rhythm of a set of bells ringing in a tower, and endows the figure of a baker “dusted with flour” with heavenly, “angelic” features.

Throughout the text, the narrator of “A Guide to Berlin” continuously demonstrates what his creator, Vladimir Nabokov, designated in “The Art of Literature and Commonsense” as “the capacity to wonder at trifles, […] these asides of the spirit,”* to see details that escape a passerby’s attention and to describe them in an imaginative way.

"EDEN"

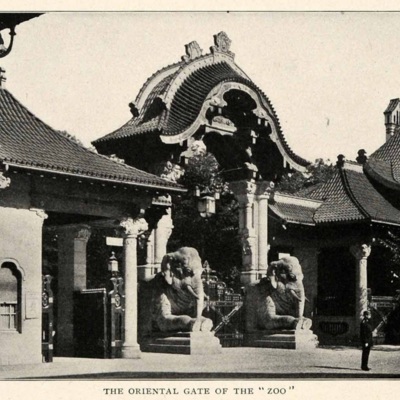

"Every large city has its own, man-made Eden on earth.

If churches speak to us of Gospel, zoos remind us of the solemn, and tender, beginning of the Old testament.

The only sad part is that this artifical Eden is all behind bars, although it is also true that if there were no enclosures the very first dingo would savage me."

He departs from the conventional trope in the very title of the section dedicated to the description of his visit there, “Eden,” and weakens the association of the zoo with Russian Berlin by pointing out in the opening sentence that the German capital is not unique.

"It is Eden nonetheless, insofar man is able to reproduce it, and it is with good reason that that the large hotel across from the Berlin Zoo is named after garden."

"THE PUB"

Having accepted that a hotel called “Eden” may be the closest an émigré can come to paradise, the narrator of “A Guide to Berlin” turns the “kindly mirrors of future times” onto himself and, by noticing his reflection in a real mirror, projects himself into the future memory of a (presumably German) boy in Berlin’s “Löwenbräu.”

""That's a very poor guide," my usual pot companion says glumly. "Who cares how you took a streetcar and went to the Berlin Aquarium?"

...

"It's of no interest," my friend affirms with a mournful yawn. "What do trams and tortoises matter? And anyway the whole thing is simply a bore. A boring, foreign city, and expensive to live in, too..."

...

"What do you see down there?" asks my companion and turns slowly, with a sigh, and the chair creaks heavily under him.

There, under the mirror, the child still sits alone. But he is now looking our way. From there he can see the inside of the tavern—the green island of the billiard table, the ivory ball he is forbidden totouch, the metallic gloss of the bar, a pair of fat truckers at one table and the the two of us at another. He has long since grown used to this scene and is not dismayed by its proximity.

Yet there is one thing I know. Whatever happens to him in life, he will always remember the picture he saw every day of his childhood from the little room where he was fed soup. He will remember the billiard table and coatless evening visitor who used to draw back his sharp white elbow and hit the ball with his cue, and the blue-gray cigar smoke, and the din of voices, and my empty right sleeve and scarred face, and his father behund the bar, filling a mug for me from the tap.

"I can't understand what you see down there," says my friend, turning back toward me.

What indeed! How can I demonstrate to him that I have glimpsed somebody's future recollection?"

Sitting in the pub with his friend, the narrator catches sight of the pub owner’s son in a small room at the far end of the tavern. On the wall above the child, there is a mirror. In it, the narrator can see his own reflection, and that mirror image—the mirror serving as a point of intersection for the parallel lines of the narrator’s and the boy’s lines of sight—represents what the boy sees as he gazes from the room into the tavern.

Metaphorical and real mirrors combine in this scene to allow the narrator to “glimpse” the boy’s “future recollection,” to imagine a future, for which the present moment in the pub will have become past. But as long as this moment is remembered, it will be connected to that future present—the present of the boy grown up, now perceived as a future. And in that recollection, there will be a violent trace of the narrator’s own even more distant past—smuggled into the future by the mirror reflection of his disfigured body.

It is perhaps ambitious to hope that the boy will indeed remember this moment, which is so extraordinary from the narrator’s perspective, and in his recreation of it, but is perhaps perceived by the boy as quite a commonplace occurrence. This scene, however, does demonstrate our narrator-guide's ability to transcend time, fully experiencing the present moment of public, measurable time, sensing both the weight of his own past and the pressure of the future).

His ability to project a recollection of himself into the boy’s future memory, and then to relive it in advance, to repeat someone else’s future recollection in the present, to experience the “now” as a moment in the past, testifies to the fact that he is able to traverse time in its “stretching-along,” to revert its flow and experience it both forwards and backwards.

In this brief moment, the narrator does seem to be plunged into “deep temporality” of existential time when the past, present, and future are united. He is able to reconcile several temporal layers and blur the boundaries of time by inscribing himself into another’s future memory, at least in—or maybe through—art.

[*Vladimir Nabokov, "The Art of Literature and Common Sense," Lectures on Literature (San Diego: Harcourt, 2002) 374.]